Photo Essay: Families Struggle for Survival in Drought-Stricken Northern Kenya

Essay and photos by Rory Sheldon

SOS Children’s Villages has mobilized emergency relief programs to address the needs of children and families in four East African countries who are struggling with drought and food insecurity.

The drought emergency response in Ethiopia, Kenya, South Sudan and Somalia focuses on food assistance, child protection, and nutritional support and monitoring. Depending on local needs, temporary shelter may be provided for at-risk children and families.

In Kenya alone, 2.6 million of the country’s 46 million people face food shortages – with nearly 360,000 children, pregnant women and breastfeeding mothers classified as acutely malnourished. Livestock losses caused by water scarcity affect both food supplies and income potential of rural families.

In Marsabit County, one of the most affected regions of Kenya, the conditions tell of a wider regional tragedy as water and food shortages pose a growing risk to children and families.

Home to an estimated 300,000 people, Marsabit County is an arid region in the north of Kenya bordering Ethiopia. The drought has been one of the worst in living memory. The remoteness of many communities complicates the ability to delivery urgently needed assistance.

Like many families across drought-stricken regions of East Africa, those in Marsabit fight a daily struggle to survive and their outlook for the future is increasingly bleak. This photo essay illustrates their struggle.

An arid landscape stretches across the Marsabit plains

More than 95% of Marsabit County’s inhabitants are pastoralists, dependent on the cattle, camels, goats, and donkeys that they herd and rear on land surrounding their villages. This land has been hit very hard. The rainy season is typically March to May, and despite shallow rainfall in early May, the 2016/17 season has been particularly dry. Forecasters warn that the drought could worsen.

Goalgallu Boru Ali

Goalgallu Boru Ali, the matriarch of a family of 13 people, lives in Dambala Fachana, a village of 5,000 inhabitants close to the Ethiopian border. In mid-May, at the height of the drought, her family lost all 50 cows upon which their livelihoods depend.

Carcasses mounted outside of Dambala Fachana

The carcasses of Goalgallu Boru Ali’s cattle are stacked in piles away from her small family house in order to avoid contact with hyenas, which enter the village in the evenings to feast on fallen livestock.

“We are lost without our cattle. What will we do now? How will my family survive?”

Many of Goalgallu Boru Ali’s children have been forced to leave home and travel great distances in order to find work. She sits with three of her grandchildren who no longer attend school. The family depends on help from neighbours. Goalgallu says, “We are lost without our cattle. What will we do now? How will my family survive?”

In Maikona, a young man slaughters the last goat from his family’s herd

In Maikona village, drought has caused the tragic loss of livestock. The price of livestock has plummeted, and in order to salvage what they can, pastoralists must slaughter their goats to salvage the meat.

Goat carcasses litter a cemetery in Maikona

The number of dead livestock “is too great to count. They fall where they die,” says Chief Guyo Isalco Elema of Maikona village, home to about 6,000 people. More than 95% of the population has been affected by livestock loss and they are now dependent on food aid from the government, he explains. “The government aid arrives only once a month and is insufficient.”

A pastoralist laments the loss of his livelihood

Jiba Okotu Halakhe is a village elder in Maikona who lost all of his livestock. “I have never seen anything like this before and I now fear for the future,” Jiba says. “We waited a long time for the rains and when rain finally arrived two weeks ago, it killed the last of my livestock.”

Children gather around the carcass of a camel in Kargi village

“When the camels start to die, you know you have a real problem,” says the chief of Kargi village, Moses Galoro. This camel died of thirst the previous day. Too heavy to move and too rotten to eat, the carcass will be left for hyenas.

Children observe the death of a camel

In better times, the camel would have fetched over US $10,000 at market. Their parents left weeks ago to find work, and these children are left to wonder what the death of this camel means for their futures.

Moses Galoro, Chief of Kargi village

One of the fears in northern Kenya is that the region will be forgotten as aid agencies focus on neighbouring countries such as South Sudan and Somalia, where internal conflicts and instability magnify the drought-related food insecurity. “Kenya has a functional government,” says Moses Galoro, chief of Kargi, a village of 12.000 people, “and we receive aid. But it is insufficient and nothing like the aid we received ten years ago from the agencies. What will happen when things get worse?”

Holathura Eisimuobanai shares this tiny hut with his wife and six children in Rarima

The Kenyan government has launched a number of initiatives to confront the grave challenges posed by this drought, including food aid and the rollout of cash transfer funds based on a credit scheme. Holathura Eisimuobanai hopes to be able to feed his six children using the credit programme. “We will have to pay them back, but we can worry about that later. For now, we must eat,” he says.

Holathura Eisimuobanai and his sons in Rarima

Holathura’s wife left with his daughters to walk to Kargi village 20 km away. There they plan to apply for a cash transfer using a government credit programme and buy food for the family. “They left three days ago,” says Holathura, “And we have not eaten anything since. I do not know when she will return, and my sons are hungry.”

Children at school in Dambala Fachana

The local school in Dambala Fachana has requested that children bring two litres of water to class with them each day as there is often a water shortage on site. Wako Liban, the school’s headmaster, admits that times are tough. “The community here is made up of pastoralists. Owing to the drought, a great number of people have moved away from this area in search of better grazing,” he says. “They take their children with them, and these kids do not return to school.”

Food aid for school children in Dambala Fachana

The Kenyan government recently delivered 500 kg of maize meal to the Dambala Fachana School. While this is very much welcomed, headmaster Wako Liban says, “It is not enough, and these deliveries are too few and far in between.”

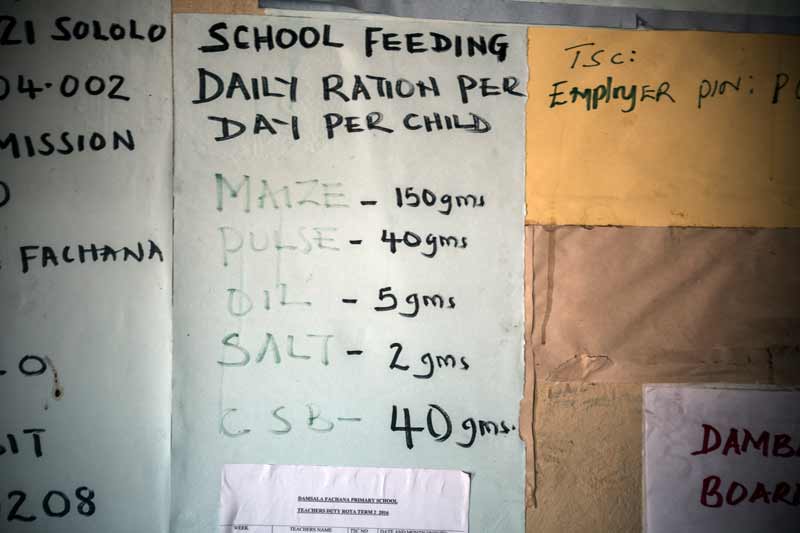

Rationing for schoolchildren in Dambala Fachana

The Kenyan government has given the Dambala Fachana School a recommended daily rationing limit for each child. Headmaster Wako Liban says, “What child can survive on 150 grams of maize meal per day? Especially when this will be the only meal they will eat that day.”

Children at Dambala Fachana

Wako Liban, headmaster of Dambala Fachana School, and Liban Gedo, the village chief, are seeking to increase daily food supplies for children. They also want to open a boarding school so that children can continue studying should their parents need to migrate to look for work as a result of the drought.

Ebenyo Moru and her five children in Marsabit

Ebenyo Moru lives on the outskirts of Marsabit town with her five children. Her family lost all of their livestock because of drought. The family depends for food on a maize field that has failed. Ebonyo’s husband left to find work in Kenya’s Turkana region and has not been heard from for over three months.

Young girl in Marsabit

A girl from a nearby family pays a visit to Ebenyo Moru’s home. Many families in the neighbourhood are struggling to meet their daily needs. Ebenyo was forced to remove her five children from school so they could help her earn money – by washing clothes on the side of the Marsabit-Moyale road.

Ebenyo Moru

Despite being ever hopeful that the current drought will end, Ebenyo Moru is pessimistic about what comes next. In a region that is prone to drought, many rural Marsabit families are struggling to survive today while facing the need to rebuild livelihoods for the future.

SOS Children’s Villages Canada is a registered charity receiving donations through the Famine Relief Fund, in response to these humanitarian crises. All donations made to the Famine Relief Fund until June 30, 2017 will be matched by the Government of Canada.

Please consider giving generously to provide critical support to these children and families.